In the Fall of 1975, Joni Mitchell and Bob Dylan came together during his infamous Rolling Thunder Revue tour. This is the story of her time with one of the most influential artists of a generation.

When the world becomes a massive mess with nobody at the helm, it’s time for artists to make their mark.

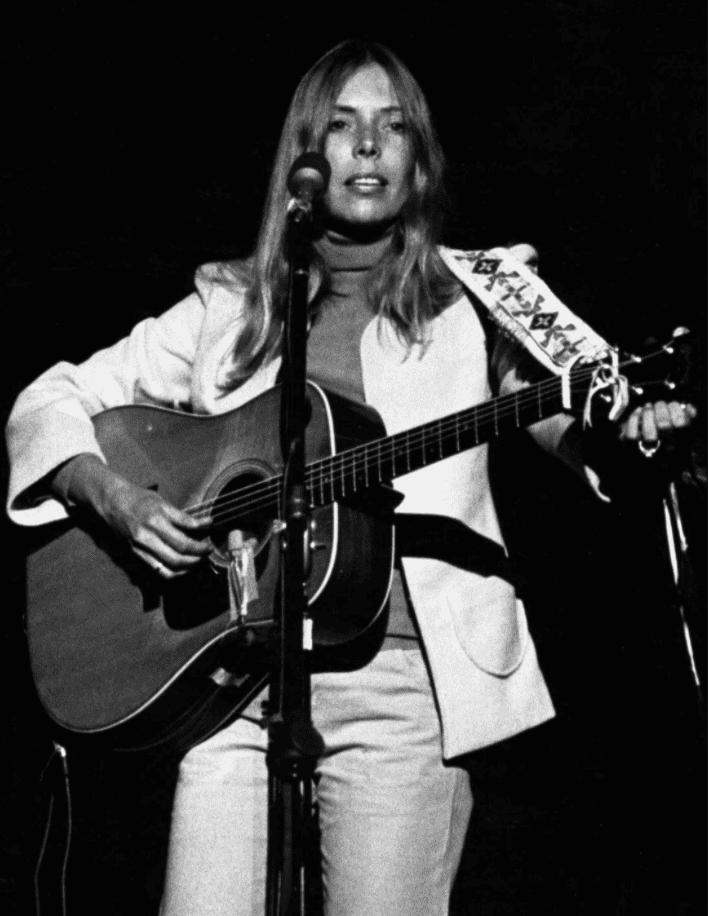

Joni Mitchell

During the 1960s, Folk Music was experiencing somewhat of a renaissance. A second coming thanks to the storied work of artists including Bob Dylan, Leonard Cohen, and Judy Collins.

Into the path forged by these musical giants steps a young singer-songwriter by the name of Joni Mitchell. Considered by critics, and pundits alike to be one of the most influential female artists of all time.

Among her many awards and accolades, her seminal1971 album Blue made it to the number 3 position in the Rolling Stone Top 500 Albums of all time in 2020.

Joni Mitchell’s life and scope of work could fill many articles on this site, but for this piece, we are focusing on her time touring with Bob Dylan during his Rolling Thunder Revue.

Bob Dylan And The Rolling Thunder Revue

In 1975, Bob Dylan’s famous Rolling Thunder Revue took to the road. Dylan claimed that the purpose of his tour was to “play for the people” and he would achieve this aim by playing at smaller venues in cities that would usually be dismissed by artists of his acclaim.

The first concert was played in Plymouth, Massachusetts – the seat of the first colonial Pilgrims – and would wander across the country until it sputtered out nearly a year after its conception.

The tour was a theatrical endeavor. After meeting Jacques Levy, a well-established theatre director and the director of the successful Broadway show Oh! Calcutta!, Dylan became fascinated with The Revue as an artistic concept: one that would enable him to revel in the American musical tradition without constraint.

The Revue, as Lou Kemp explained, traveled as a “caravan” for musicians, artists, writers, and filmmakers.

Along for the ride were names such as Joan Baez, Roger McGuinn, Gordon Lightfoot, Ramblin’ Jack Elliot, actress and singer Ronee Blakley, poet Allen Ginsberg, long-time friend Bob Neuwirth, as well as playwright Sam Shepard (who would later help write Dylan’s film Renaldo and Clara). Invited were names such as Patti Smith and Bruce Springsteen, who both amicably declined.

Embed from Getty ImagesJoni Mitchell And Bob Dylan

Joni Mitchell joined the tour in Connecticut, for a show on the 13th of November in Veteran’s Memorial Coliseum and traveled with the troupe for the greater part of the first leg.

Among the many highlights of the tour were Bob Dylan and Joan Baez performing on stage together. Joan was one of the first artists to perform Bob Dylan’s music and was pivotal in his music becoming widespread due to her popularity as a recording artist.

During the first concert in Plymouth, Bob Dylan spontaneously called everyone on stage to perform the Woody Guthrie song “This Land Is Your Land. According to Joni, the spirit in the room was extremely warm, and it prompted her to stay with the troupe for the rest of the tour.

In an interview with Mary Aikins in 2005, Mitchell describes her time accompanying Dylan and his followers. By her account, the tour was not a caravan or a musical cavalcade but a circus:

I went on Rolling Thunder and they asked me how I wanted to be paid, and I ran away to join the circus: Clowns used to get paid in wine — pay me in cocaine because everybody was strung out on cocaine.”

Joni Mitchell (2005).

Despite this, Mitchell appreciated the opportunity to be “an observer and a witness to an incredible spectacle” (her words, taken from an interview with Cameron Crowe in 1979). She recognized the event as a significant and formative experience that would come to influence the album she would come to release a year later, Hejira.

In 1988 journalist Timothy White talked with Joni concerning Hejira. She mentions that:

“Hejira came out of another of my sabbaticals, another time when I flipped out and quit show business for a time. This instance was in ’76. I’d been out with Dylan’s Rolling Thunder Revue, which was an amazing experience, studying mysticism and ego malformation like you wouldn’t believe. Everybody took all of their vices to the nth degree and came out of it born again or into A.A.

Afterward, I drove back across the country by myself, and I used to stay in places like light-housekeeping units along the Gulf Coast. I gave up everything but smoking, and I’d run on the beach and hit health food stores. In New Orleans, I wore wigs and pawned myself off as someone else. Meanwhile, nobody knew where I was.

I’d do these disappearing acts. I’d pass through some seedy town with a pinball arcade, fall in with people who worked on the machines, people staying alive shoplifting, whatever. They don’t know who you are: “Why are you driving that white Mercedes? Oh, you’re driving it across the country for somebody else.” You know, make up some name, and hang out. Great experiences, almost like the prince and the pauper.

So whenever possible during these breakdowns in my career I would pawn myself off as someone else, or go to some distant clime and intentionally seek out a strata of society I was sure I would never have gotten near otherwise.”

The Influence Of Chögyam Trungpa

Joni did not arrive at the decision to distance herself from the chaos of The Revue and the entertainer culture that had infiltrated the mainstream music scene alone. Her attempts to experiment with ego and surrender her vices were inspired by an acquaintance made on the tour:

It was Chögyam Trungpa who snapped me out of it just before Easter in 1976. He asked me, “Do you believe in God?” I said, “Yes, here’s my god and here is my prayer,” and I took out the cocaine and took a hit in front of him. So I was very, very rude in the presence of a spiritual master.”

Joni Mitchell

Trungpa was a spiritual teacher of Tibetan Buddhism, focusing on the non-sectarian dissemination of Buddhist teachings, particularly meditation practices. In an interview for Readers Digest, Joni later explained that for three days after the encounter she “was in an awakened state”:

The thing that brought me out of the state was my first “I” thought. For three days I had no sense of self, no self-consciousness; my mind was back in Eden, the mind before the Fall. It was simple-minded, blessedly simple-minded. And then the “I” came back, and the first thought I had was, Oh, my god. He enlightened me. Boom. Back to normal — or what we call normal but they call insanity.”

Joni Mitchell

The visit was immortalized in her song ‘Refuge of the Roads’ and the editorial note that appears on the record – Hejira – reads:

I consider him one of my great teachers, even though I saw him only three times. […] [Later], at the very end of Trungpa’s life I went to visit him. I wanted to thank him. He was not well. He was green and his eyes had no spirit in them at all, which sort of stunned me, because the previous times I’d seen him he was quite merry and puckish – you know, saying “shit” a lot.

I leaned over and looked into his eyes, and I said, “How is it in there? What do you see in there? And this voice came, like, out of a void, and it said, “Nothing.” So, I went over and whispered in his ear, “I just came to tell you that when I left you that time, I had three whole days without self-consciousness, and I wanted to thank you for the experience.” And he looked up at me, and all the light came back into his face and he goes, “Really?” And then he sank back into this black void again.

Joni Mitchell Writes A Song About Bob Dylan

Joni Mitchell and Bob Dylan appear to have a strained relationship, despite sharing the stage together on several occasions. Shortly after touring with Dylan for the Rolling Thunder Revue, she shared her frustration in the form of a song titled “Talk To Me”.

The song features lyrics including:

“Is your silence that golden?

Are you comfortable in it?

Is it the key to your freedom,

Or is it the bars to your prison?”

Despite obviously being targeted at Dylan, and her frustration at the lack of communication between them while on tour, she was wisely veiled with her choice of words so as to not aliente a fan base that worshipped them both.

The Martin Scorsese Film

In 2019, acclaimed director Martin Scorsese brought his long-anticipated film about The Rolling Thunder Revue to the big screen. Upon release, Chris Willman from Variety described it as “Part documentary, part concert film, part fever dream… a one of a kind experience from Martin Scorsese”

Scorsese masterfully mixes together archival footage from the Rolling Thunder Revue, contemporary interviews with prominent figures from the tour, as well fictional interviews of actors playing characters that were not involved with the production, or tour at all.

Despite the film’s popularity, it has received some criticism around Scorsese’s use of “creative license” in the telling of the story. We have listed some of the more glaring errors below.

Congressman Jack Tanner Is Based Off A Fim Character

During the movie, Congressmen Jack Tanner boasts about using his political connections to get into one of the shows on the tour.

But there was no Congressman Jack Tanner, he was played by actor Michael Murphy and they used the name, Jack Tanner, from a 1988 election campaign mockumentary called Tanner ’88.

The Mysterious Stefan Van Dorp Does Not Exist

The Rolling Thunder Revue contains interview footage of Stefan Van Dorp, a mysterious filmmaker who claims to have filmed the entire tour, yet never received credit for the work.

In reality, while on the tour, Dylan was filming for his movie, Ronaldo and Clara, and it is this footage that comprises the bulk of the Rolling Thunder Revue film.

Stefan Van Dorp was played by actor Martin von Haselberg, who happens to be married to Bette Midler.

Sharon Stone Did Not Join The Tour As A Teenager

For reasons only known to Bob Dylan and Martin Scorsese, they chose to manufacture a relationship between Dylan and a teenage Sharon Stone. They supposedly met when she was trying to get into one of his concerts and the folk singer took a liking to her.

Despite both Stone and Dylan being interviewed about their relationship during the film, none of it is true, and the images of them together are photoshopped.

Bob Dylan Did Not Get Inspired By Seeing A Kiss Concert

During the movie, Dylan is seen wearing white face makeup on several occasions. During an interview, he states that he got the idea after seeing the rock band Kiss perform in Queens.

However, the only time Kiss played in Queens was in 1973 and at that stage, they were just starting out as a band and playing in local dive bars.

It’s highly doubtful that Bob Dylan was present at one of these tiny clubs for an unknown band.

Frequently Asked Questions

How Old Is Joni Mitchell?

Born in 1943, Joni Mitchell is 78 years old

When Did Joni Mitchell & Bob Dylan Perform Together?

Joni Mitchell and Bob Dylan performed together for the final leg of the Rolling Thunder Revue, from the fall of 1975 onwards.

Who Toured With Bob Dylan & Joni Mitchell For The Rolling Thunder Revue?

Besides Joni Mitchell and Bob Dylan, the Rolling Thunder Revue included Joan Baez, Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, Scarlet Rivera, and Mick Ronson.

Who Was Joan Baez?

“The Queen Of Folk”, Joan Baez released over 30 albums and was one of the first artists to perform songs written by the young Bob Dylan.

Their relationship developed over several years, often performing together on stage.

For those who are interested, the lyrics to ‘Refuge Of The Roads.’

I met a friend of spirit He drank and womanized And I sat before his sanity I was holding back from crying He saw my complications And he mirrored me back, simplified And we laughed how our perfection Would always be denied "Heart and humor and humility" He said, "will lighten up your heavy load" I left him then for the refuge of the roads I fell in with some drifters Cast upon a beach town Winn Dixie cold cuts and highway hand me downs And I wound up fixing dinner For them and Boston Jim I well up with affection Thinking back down the roads to then The nets were overflowing In the Gulf of Mexico They were overflowing in the refuge of the roads There was spring along the ditches There were good times in the cities Oh, radiant happiness It was all so light and easy 'Til I started analyzing And I brought on my old ways A thunderhead of judgment was Gathering in my gaze And it made most people nervous They just didn't want to know What I was seeing in the refuge of the roads I pulled off into a forest Crickets clicking in the ferns Like a wheel of fortune I heard my fate turn, turn, turn And I went running down a white sand road I was running like a white-assed deer Running to lose the blues To the innocence in here These are the clouds of Michelangelo Muscular with gods and sungold Shine on your witness in the refuge of the roads In a highway service station Over the month of June Was a photograph of the earth Taken coming back from the moon And you couldn't see a city On that marbled bowling ball Or a forest or a highway Or me here, least of all You couldn't see these cold water restrooms Or this baggage overload Westbound and rolling, taking refuge in the roads

Written by Tom Westhead

Similar Stories

- Sara Dylan – Muse & First Wife of Folk Rock Legend Bob Dylan

- Karen Dalton – The Powerful Folk Singer You’ve Probably Never Heard Of

- Above the Strip – An Introduction to Laurel Canyon

- The Alice Cooper Fact Sheet – 5 Things You Need To Know - January 12, 2023

- Everybody Knows The Words, But What Is Hotel California About? - April 29, 2022

- What Is The Meaning Of Stairway To Heaven: Led Zeppelin’s Amazing 1971 Musical Epic? - April 24, 2022